|

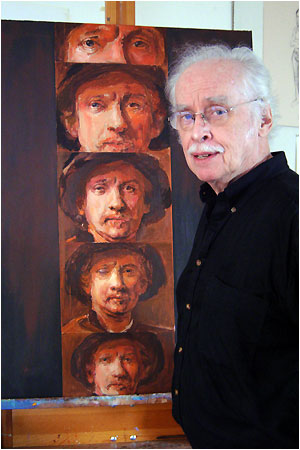

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Russell Connor was born June 15, 1929 in Cambridge,

Ma., and passed away on March 24, 2019.

The following is the

biography he wrote for this website.

“It’s OK to be an artist, if you can paint like Rembrandt.” I’m sure my father said many wise things when I was growing up in Arlington, Massachusetts in the thirties and forties. Sad to say, this is one of two I remember (the other came when, as a happy young child, I set out to walk on a Cape Cod beach. “Remember, however far you go, you have to walk back the same distance.” Considering how few children were likely to need this caution, it suggests Dad understood his youngest son pretty well.

The Rembrandt admonition came when I wanted to go to art school. I had been a cartoonist for the school paper, and won praise from the family for the precision of a drawing copied from a Life magazine cover (advice to parents: be careful what you praise). Other fathers might have responded, “It’s OK to be an artist, as long as you have another way to make a living.” In the post-WWII years, Massachusetts College of Art in Boston was full of security minded veterans on the GI Bill –after the first two years of a smattering of everything, from anatomy and perspective to illustration and pottery, most of the vets majored in Education, aiming to become public school art teachers, or in Commercial Art. I went into the small Drawing and Painting department, painting every day from the model or still life set-ups, in a manner best described as Fifth Generation Impressionism. I had little awareness of developments in New York, where First Generation Abstract Expressionism was about to earn international recognition for American art. The Rembrandt admonition came when I wanted to go to art school. I had been a cartoonist for the school paper, and won praise from the family for the precision of a drawing copied from a Life magazine cover (advice to parents: be careful what you praise). Other fathers might have responded, “It’s OK to be an artist, as long as you have another way to make a living.” In the post-WWII years, Massachusetts College of Art in Boston was full of security minded veterans on the GI Bill –after the first two years of a smattering of everything, from anatomy and perspective to illustration and pottery, most of the vets majored in Education, aiming to become public school art teachers, or in Commercial Art. I went into the small Drawing and Painting department, painting every day from the model or still life set-ups, in a manner best described as Fifth Generation Impressionism. I had little awareness of developments in New York, where First Generation Abstract Expressionism was about to earn international recognition for American art.

In Korea and Japan during and after the Korean War, I was surprised to be esteemed simply for being an artist, converted to abstraction under the influence of modern Japanese calligraphy (hurdling post-impressionism, cubism and expressionism), had my first exhibition in Tokyo, fell in love with and married a lovely woman named Toshiko.

My own GI Bill years at Yale with the Bauhaus master Josef Albers taught me about color. Just as important were summers back in Massachusetts, where a job as night watchman at Harvard’s Fogg Art Museum became a lovely chance to study great art up close, as well as a haunting, prophetic invitation to fantasy, imagining figures escaping from their frames in the darkness to play with their neighbors.

Then, the dream of every young American artist since the 19th century, a year in Paris, overwhelmed by its beauty, and treading too reverently in the steps of my heroes.

Waking from a dream, one needs a job, once more in a museum. This time in the Education Dept. of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, as writer/host of a weekly televised gallery talk called Museum Open House, produced with WGBH. Broadcast after Julia Child’s show and seen around the country, I enjoyed performing as an Instant Expert on The Art of the World. Untrained as art historian, preparing a half-hour script each week for four years inevitably pushed painting into the back seat.

Fortunately I quit before it moved to the trunk.

But I had fallen under the spell of another monster, television. I dreamed of exploring its own potential as an art form. After a fateful encounter with the Korean video art pioneer Nam June Paik, I organized the world’s first museum show of video art at Brandeis in 1970, and spent the decade getting grants for video artists, collaborating with Paik, William Wegman and Bill Viola, and making films on art for television. That led to a job as Director of Education at the Whitney Museum of American Art, and to a surprising revival in the eighties of my life as a painter.

This awakening, one of life’s real Second Chances, came from a decision to draw on all that time spent in museums and television, my adventures in the “popularization” of art, rather than consider them wasted as a painter. In spite of the tremendous profusion of art images since WWII, most people have hesitation attributing which work to which artist. I decided to make this muddled mental museum my arena, my playground. Copying one masterpiece can be boring – putting two together makes a new narrative and a new composition. Borrowing an effect from TV and video art called Chroma Key, in which one can mask out and replace any backgound, I was able to create fantasy and mystery. When I combined Rubens and Picasso, or put Manet’s Dead Toreador on the floor beside his Olympia and called it Love and Death, I knew I was launched on an exciting quest – how to copy and be original, how to be serious and make people smile at the same time.

Russell Connor

mail@russellconnor.com

|